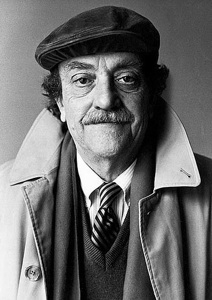

Kurt Vonnegut, 1922-2007

by Matt Hanson

originally published in Flak Magazine

Say toodle-oo to one of the last remaining wise men of American letters.

"I have long felt that any reviewer who expresses rage and loathing for a novel is preposterous. He or she is like a person who has put on full armor and attacked a hot fudge sundae or a banana split."

-New York Times Book Review 1985

Deep in the small scrolling columns of credits at the end of Keith Gordon's 1996 film "Mother Night" a character, or better yet a fragment, is indicated. "Sad Man On Street" is the second listing in the filmography as actor of Kurt Vonnegut, Jr, late of Indianapolis, Indiana. This modest, funny, noble distinction may be the most accurate way to contextualize the life, work, and presence of someone who was one of the last remaining wise men of American letters. Not surprisingly, it wasn't a speaking part. More than that, you wouldn't have noticed it unless you had heard about his cameo beforehand, and it wouldn't have heard of it in the first place if you didn't place any value in attention paid to sad old men on the street. Kurt Vonnegut was one of these, in the noblest and wisest way possible, in spirit as much as in prose form.

One of the really and truly good human beings of postwar American letters has now shuffled off this mortal coil for keeps. And, as he might have been happy to report, it was about damn time. (I have never heard of someone else angry at Big Tobacco for not having killed them off quicker.) Like most people approximating decency, he had his own snake bag of contradictions. His fiction and his bearing was alternately hopeful but despairing, sad but sweet, angry but forgiving, sarcastic but never cruel. Human, but never more than mortal. True leaders don't dictate, they are simply & calmly followed, just as originators never succeed in escaping imitation. There's something about the people who don't believe in anything which makes everyone believe in them. Reading him throughout his multigenerational career, it's easy to have trusted in his wisdom.

One of the reasons for this is very plain- he'd seen it all.

He endured the suicide of his mother (on mother's day) shortly before entering World War II as the child of third generation German-American Jewish parents and, of course, was subject to the firebombing of Dresden by the Allied forces, before being forced by the Nazis to collect corpses strewn about everywhere. Then he came home. After absconding from the University of Chicago he worked in public relations for General Electric and began working on science fiction stories for the emerging market. In twenty years, he would become the smiling, stony, sweethearted conscience of at least a couple generations, and without seeking the title at all. He'd already more than earned his right to be bitter, and offered the betrayed world his own small and bittersweet hope.

And, God bless him, he kept the faith. Through it all, he could do two things to maintain and survive- laugh like a firecracker ("Napalm came from Harvard. Veritas!"), and say something modestly beautiful and beautifully modest, like: ("I never met a writer's wife who wasn't beautiful.") These alternating impulses- to mock the bastards who run this planet off its axis, and alternately to enjoy the grace in quiet places and forgiving moments- made him tick as a writer of prose fiction, sparked his political fervor, and most likely propelled him further as a human being. After his celebrity had caught on, and Slaughterhouse 5 had become a bestseller, he was once approached by some querulous reporter and asked how it felt to be an outsider (like his literary peers Ginsberg, Heller, Baldwin and Mailer) taking on 'the literary establishment'. For years afterward, his response- "If we aren't the establishment, who is?"- was the strongest string connecting the movements of American letters from post-war to the present.

So it goes. Hi ho. Selah. Hey presto! Prosperity is just around the corner. These and other phrases (billboard ready) were always a unique, meek and puckish reminder that bubbles of overcomplexity- granfaloons- are always meant to be popped. He gave the reader as well as himself a small refrain from the cataclysms and catalysts of his novels. After an apathetic mad scientist accidentally sets the stage for the destruction of the planet, sibling geniuses repeatedly made whoopie, anxious and sex-mad car salesmen went off the deep end, shouting about leaks in the universe, the reader usually needed a little breather. Although the whimsical repetitions of near-nonsense were arguably the most annoying tics as a writer of prose nobody- but nobody- could be allowed more slack and breathing room as a fellow sufferer on this doomed marble than Mr. Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

And, not to be forgotten, a little chuckle clears the brain. Hi ho.

Reading his fiction, the outlandish, madcap, morbid, poignant chronicles of one soul whistling through a coal mine, it's hard to imagine someone fathering them who doesn't ultimately love this world- its ideas, his children, aside and apart from the foul and awful capabilities. It wasn't hard to imagine him taking you by the arm and leading you through the rancid madness of a planet run by fools, dupes, and apes and eventually stopping alongside the mayhem to sit a spell on a porch with a cool glass of lemonade in the bright, warm, afternoon sun. He wanted to skylark- a military term of disapproval for lazy or irresponsible behavior- and for you to skylark with him. He would have been a wonderful Buddhist.

"If this isn't nice, what is?" Vonnegut never forgot to remind you to "keep score like that"- the word choice is telling here. Beauty redeems, and he never let us forget it. He didn't associate music with God for sentimental, entertainment value.

However, as he once quietly noted, he had a couple wives who left him for being "too depressing". He chain-smoked pall malls for several decades and referred to it as "a classy way to commit suicide." He once remarked that saying "I Love You" to someone was like pointing a loaded gun in their face. He wrote humbly and bravely about a suicide attempt in 1985. For myself, I can't bear to try and re-read Mother Night, though I've wanted to a hundred times. The first time through, I caught a whiff of some mighty dank and deep holes in the human universe that I have no stamina to re-visit once again. He spoke frankly- and obsessively- about madness, dehumanization, death, sleaze, and despair. After traveling in Biafra in 1974, he wrote that he made three short barking noises in lieu of tears. This was not a man who would have made a good hippie.

It's been rightfully pointed out that Vonnegut's great forbearer was Mark Twain. They shared a cynicism, a sarcasm, a folksy and democratic liberalism that didn't preach and yet had resonances of the Old Testament, a smoking addiction, a haircut, and an ancient mariner sense of solitude while being in the public eye. It's also worth pointing out that he had more than a little Voltaire in his blood, as well- the outrageous satires, the constant perusal of society's dirty laundry, and the rage against a distant God in a desolate, indifferent world. But a case can be made for another great forbearer in the form of Albert Camus. Vonnegut walked around and around the circle of the inferno, pushing a rock which pushed back, and yet you can't help but remember that he made himself endure.

This fed into his political vision. Never afraid of earnestly naming his creations, and other than Billy Pilgrim and Eliot Rosewater he also had characters named Eugene Debs Hartke and Leon Trotsky Trout. It's not that he carried a banner, it's that he caught the spark which has been passed from person to person under the American mainframe and carried it well. I can also be sure that I am not the only one who, while earnestly perusing God Bless You, Doctor Kevorkian in the tiny town library one summer's day, felt a keen but indistinct stirring when I read the famous quote from Eugene V Debs (another Hoosier Socialist) Vonnegut saw fit to include: "If there is a lower class, I am in it. If there is a criminal element, I am of it. If there is a soul on prison I am not free." A more eloquent evolution of the Sermon On The Mount, and at the expense of the Bourbon Bible bangers who never leave us, would be hard to ask for. Vonnegut was`someone who saw- correctly- that in America there are only two political parties, the winners and the losers, and he absorbed and promoted Socialism in the best way possible. Camus once wrote that it was the duty of thinking people to not be on the side of the executioners. Kurt Vonnegut was never on the side of the executioners.

Vonnegut will not fade quickly from our collective memories because he was, without question, the real deal example of what our culture has been trying like hell to achieve and can't quite seem to grasp: a unity of wisdom & realism. Foma- a term coined by Vonnegut and defined as a harmless untruth- is everywhere. We try and try- watch someone you know describe something they've experienced as "interesting" with an eye roll and a shrug and you'll see what I mean- to convince ourselves to act like our culture and generation has seen it all. We haven't. Not by a long shot. Part of the enduring legacy of Kurt Vonnegut is that he had. And he loved us all, in his way, even as he was dying to head home.