Redemption Song: A Life of Joe Strummer

by Matt Hanson

originally published in Flak Magazine

Growing up in the suburbs in the mid to late 90's, music wasn't everything. It was the only thing. Part of the awful ramifications of mid adolescence was the desire to cordon off most varieties of interpersonal relationships in terms of what tuneage one fancied. I think I understand why people got their asses kicked in midcentury swinging London over whose clique preferred The Beatles to The Rolling Stones. It's an outsider talisman, a relic, and a coat of arms.

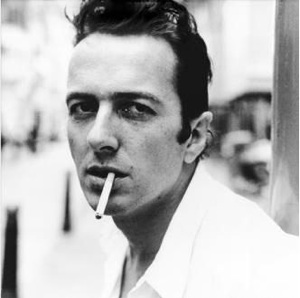

My hometown burned with boredom, then and now. I remember sitting and sweating and ca-chunging soberly through the little boxes and kept grass in my innocuous, prosperous suburb with Combat Rock getting warm in the disc changer. It stammered and raged through the rattling speakers of the immortal heirloom van driven by a spastic comrade. Strummer was our guy. No pranksters we, not athletes or intellects or hooligans (I don't think anyone seriously drank until college). We were lightweights. We dug nobility. We could see it in his eyes. He was enough of a rebel poet to appeal to the latent creativity and political consciousness slowly dawning on the horizon. That was what drew us to the man formerly known as John Mellor, a rascally diplomat's son turned elder statesman of counterculture. We weren't the only ones.

One of the most arresting scenes in Dick Rude's great indie biopic Let's Rock Again is one which nobody really ever saw. On a sunny day in southern California, a snaggletoothed, scrawny, balding Englishman with wide, piercing eyes and a corny leather jacket walks around a sunlit street quietly handing out small pieces of paper. He buttonholes pretty much everybody who happens by: zitfarm high school dropouts, lunching businessmen, bums, cops, soccer moms, quizzical middle aged immigrants and unselfconsciously, unheedingly asks them if they like rock and roll music. You see, there's a show on tonight, and he's with the band...

The best part is that no one gives a shit. Everyone sort of nods and smiles, shakes his hand, and aimlessly departs. The handmade concert fliers get tossed as Joe motherfucking Strummer distractedly lights a cigarette and flags down another passersby. He doesn't see the joke, or at least he doesn't laugh. He's got a room to fill. I don't recall if he actually sold out the show but since he had to buzz the intercom of the local radio station from the parking lot to get airtime (another great scene: "My name is...I was in The Clash!" "What?" "The Clash!" "Uhm, we'll send someone down") I have my doubts.

This is very much the picture we get of the man and his life from Chris Salewicz's stimulating, brisk, and wonderfully detailed labor of love. Salewicz knew the man personally (Strummer called him "sandwich") and was known to have drank and smoked with him authoritatively for years longer than many could claim. He even came to his aid once when street thugs tried to raid the house. This was embarrassingly recounted by Joe to strangers whenever he wanted to break the ice. What we get in these pages is a universal Joe. A bit of a man's man, given to occasional macho exhibitions and arrogant fury. More than a little bit of a child: he decided one day, point blank, to run the Paris marathon for sheer kicks. Essentially a poet, or at the very least poetic. Rent Alex Cox's cult classic Straight To Hell to see him improvise mesmerizingly incoherent imagery to the camera while he practices his pistol aim, back lit by campfires in the Spanish night. He once insisted, in fact, on a drunken road trip to Lorca's grave (a personal hero and the subject of "Spanish Bombs") burned a hand rolled spliff to his fingertips, sat alone on the grass, and wept like a baby.

It's the details which make our stories. Salewicz is clever enough to know this, and he provides a lucid narrative to let the life tell itself. And he noticed, and remembered, everything. Strummer carried all his belongings in innumerable plastic shopping bags long after he settled down and actually had a place to put his stuff. When studio recording, he made little forts out of desks, chairs and blankets and slept there night after night. He put so much grease in his ducktail hairdo that it was constantly crammed with dandruff, dust, and lint. Bums and locals in whatever country he visited became his best friends in the world in the course of an afternoon and drank on his tab till dawn. He named his beloved daughters Lola and Jazz. During his obsession with Woody Guthrie he answered only to the name "Woody". He was well known for honoring every ticket, and pulling in stowaways from the parking lots outside the venues, signing autographs for hours after shows, and not quite noticing how it wasn't rock star behavior.

It's great to see him being awkward and dorky. As a young man he tried his hand at gravedigging in Wales. The sturdy professionals in the lot mocked the hell out of his inability to dig more than a foot or so into the ground. After that, it was garbage detail for pennies on the dollar. He was an incompetent shoplifter, once letting a 12 pound frozen turkey tumble out of his overcoat in front of the register. As a teenager he and his friends dressed up like Indians and hung out for hours in front of Parliament. In the 80's his solo career officially bottomed out so he decided to go up and down Europe and the coast of Scotland for a busking tour. His version of Gene Vincent's 'Be Bop A Lu La' was the showstopper. He played for tips and tipped big. This is to only give away a smidgen of the story, though. Part of the fun of this book is to pick out one's favorite anecdotes and there are plenty to go around. That's the kind of man Joe Strummer was.

One of the interesting things about Salewicz's take on the whole Strummer legacy is that he is not presented as a perfect soul. Salewicz is wise enough to show this plainly. He could be quite arrogant when the mood struck him, berating his bandmates and snapping at loved ones. I was surprised to find he was indeed the one who fired Mick Jones (the Paul to his John) under insistance from Kosmo Vinyl. Apparently he had a very impressionable, pushover aspect to him that led him to be swayed by various authority figures throughout his life. A bully at boarding school, he never got over the humiliations he inflicted on lesser lifeforms and brooded on it later on in life. He cheated on his first wife and occasionally bragged about it.

What redeems him, however, is the fact that no matter what he did his conscience would howl at him and drive him to adapt and reform his life as he grew older and became a kind of punk statesman. It gave him the humilty of a man who has lived long enough with his sins to have deep wells of native sympathy from which to draw. Listen to the obscure gem "Broadway" off of Sandanista and hear him describe it. Listen to his duet with Johnny Cash (another hero of his who accomplished the same thing) on Bob Marley's "Redemption Song" to hear this in stereo. Listen to the way he digs in, defiantly and unbowed, into Junior Murvin's "Armageideon Time" and you can feel his politics without program. There was a reason people followed him; he knew he was no one to be followed.

Whatever one's image of Joe Strummer might be, it's probably accurate. He was indeed lonesome and charming and noble and arrogant and gentle and brilliant and kind. At least, when you caught him at the right moment. Paul Simeonon mentions that Joe kept massive amounts inside. He was known to respond to a simple query on how his day was going with a mumble about his mother's mortal illness. And then never bring the topic up again. His life was a splendid chaos on purpose.

His beloved older brother, when still monstrously young, became clinically depressed. Slowly he sank deeper and deeper into isolation and despair, briefly embraced full blown Nazism, and finally took his own life. Obviously, Joe was haunted by this his whole life. He'd studied Cherokee philosophy early on and learned that when faced with a difficult decision to always take the most reckless path possible. When he died it was uncovered that he'd unwittingly possessed a congenital heart defect. A tube was wound the wrong way, meaning he could have easily died at any moment. He's decided early on to live for two. It's very much to his credit that he did. And he had the scars and stories and words of music to prove it. And now we have a weighty tome to bear witness to his ballad, which turns out to have really been about redemption after all.